Digital Time

How digital systems multiplied temporal signals into alerts, notifications, and manufactured urgency.

How Humans Read Time — Part 3 of 5

→ Series overview

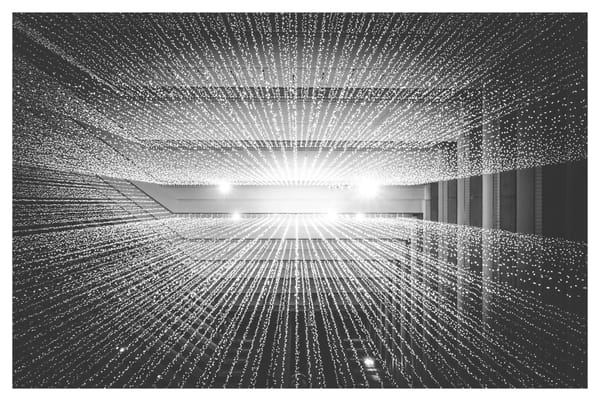

Digital time didn't just make mechanical time faster—it made time ambient.

The mechanical clock lived in specific places: tower squares, factory walls, wrists. You had to look at it. You controlled when to check.

Digital time is everywhere, always visible, and increasingly proactive.

Screens show time in the corner. Notifications arrive with timestamps. Calendars send alerts. Fitness trackers count seconds. Every app, every device, every interface carries its own temporal signal—and most of them demand attention rather than waiting to be consulted.

This isn't incremental refinement of the mechanical clock. It's a fundamental shift in how time reaches you.

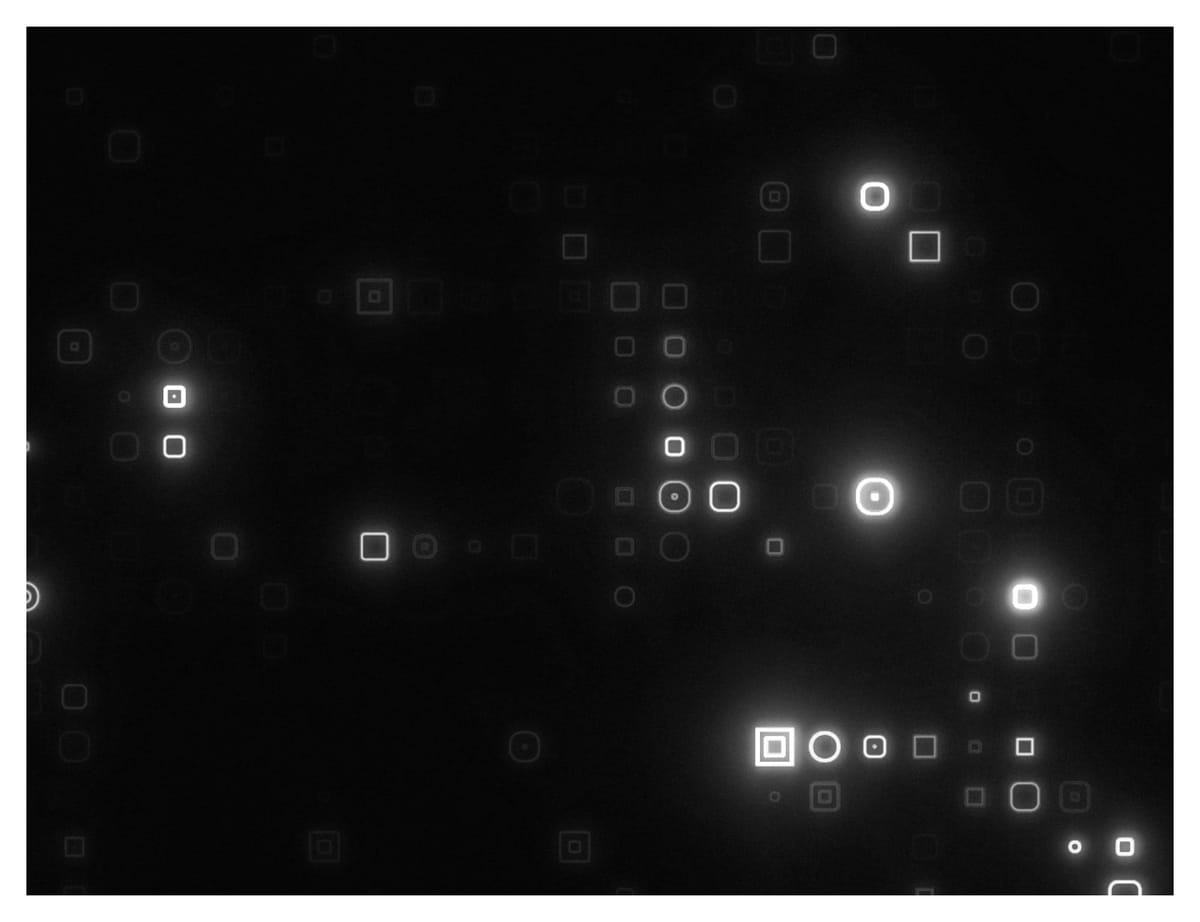

Mechanical time abstracted time from environment. Digital time multiplies temporal reference frames—creating dozens of independent timers, countdowns, alerts, and deadlines operating simultaneously, none of which know about each other, each claiming urgency, each fragmenting attention.

The result: you're not reading one clock anymore. You're navigating multiple independent temporal signals operating simultaneously, most of which you didn't ask for.

What Digital Time Actually Does

Digital time doesn't wait to be consulted—it interrupts to announce itself.

The mechanical clock was passive. It displayed time continuously, but you decided when to look. The factory bell rang at scheduled intervals, predictable and finite.

Digital time is active. Notifications arrive unscheduled. Calendar alerts fire regardless of what you're doing. Email timestamps create implicit urgency ("sent 2 minutes ago" suggests expected response speed). Messaging apps show "typing..." and "read" status, turning every delay into visible information.

This isn't malicious—it's necessary for asynchronous coordination.

When people work across time zones, notifications bridge the gap. When teams operate remotely, timestamps make delays legible rather than invisible. When systems need to coordinate without real-time presence, proactive alerts replace the need for constant checking.

The design challenge is real: how do you coordinate hundreds of people across time zones without constant meetings? Notifications are a partial solution. The problem isn't that they exist—it's that they multiply without hierarchy, and most systems lack mechanisms for users to impose coherence on competing demands.

The problem isn't that these signals exist—it's that they multiply without hierarchy.

Every app, every service, every platform creates its own temporal demands. Calendar alerts, message notifications, delivery updates, payment reminders, social media pings, fitness goals, subscription renewals—each operates independently, each assumes it deserves immediate attention.

This shifted temporal orientation from scheduled rhythm to episodic interruption. Mechanical time imposed linear schedules with predictable intervals. Digital time operates episodically—alerts arrive whenever triggered, creating no discernible pattern, no rhythm to internalize. You can't develop a temporal sense for random notifications the way you could for hourly bells.

The shift: from episodic time-checking to continuous temporal noise.

Mechanical time fragmented attention into scheduled interruptions (clock bells, shift changes). Digital time fragments attention into unscheduled interruptions—each notification a temporal claim demanding immediate context-switching.

Your phone doesn't just tell you what time it is. It tells you:

- What you should be doing now (calendar alert)

- What you failed to do earlier (overdue reminder)

- What someone else wants from you (message notification)

- How long you've been doing this (screen time tracker)

- How long until the next demand (countdown timer)

Each of these is a separate temporal reference frame, operating independently, often conflicting.

The mechanical clock gave you one authoritative time signal. Digital systems give you dozens, and you're expected to navigate all of them simultaneously.

Frictionless Fragmentation

Digital time makes it trivially easy to create temporal commitments—and impossible to manage their collective noise.

Setting a reminder takes seconds: tap, type, set time, done. Creating a calendar event is equally frictionless. Subscribing to notifications requires one click. Each individual temporal signal seems reasonable when created.

The problem emerges in aggregate.

Frictionless reminder creation produces incoherent temporal demand.

You set a reminder for a call at 2:00 PM. Your calendar alerts you to a meeting at 2:15 PM. Your task app notifies you that three items are overdue. Your email app shows 12 unread messages from today. Your package tracker announces delivery in 45 minutes. Your fitness app reminds you that you haven't moved in two hours.

None of these systems know about each other. Each operates independently, assuming it's the only temporal demand on your attention.

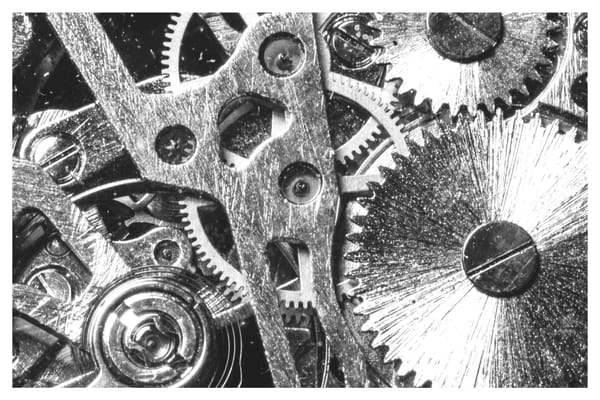

The mechanical clock had one reference frame. Digital time has dozens—but they don't synchronize, don't negotiate priority, and don't acknowledge each other's existence.

This creates temporal fragmentation at the infrastructure level.

It's not just that your day is chopped into small pieces—it's that the pieces don't fit together coherently. You can't read the overall temporal pattern because there isn't one. There are only overlapping, competing, independently-generated temporal demands.

The ease of creating reminders means people create them constantly, without considering the cumulative load. "I'll just set a reminder" becomes reflexive. Each reminder made sense in isolation. Together they create incomprehensible noise.

Digital calendars allow double-booking, triple-booking, infinite-booking—nothing prevents you from committing to contradictory temporal obligations because each system only knows its own slice.

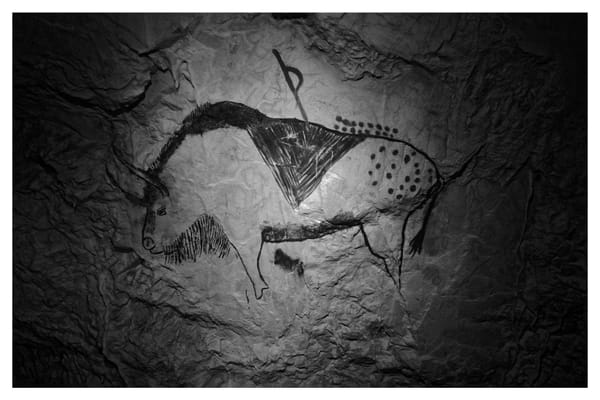

Pre-instrumental time was coherent but coarse—environmental signals converged into readable patterns. Mechanical time was coherent and precise—one synchronized clock everyone referenced. Digital time is precise but incoherent—multiple high-resolution signals operating out of sync, creating obligations faster than you can execute them.

The tools for setting temporal markers became frictionless. The result is chaos.

These signal types also differ in temporal resolution. Digital systems track microseconds. Environmental patterns operate in hours and days. Organizational rhythms span weeks and quarters. Temporal literacy means knowing which resolution matters: when you need minute-level precision for coordination versus when daily granularity suffices for execution.

But asynchronous capability compressed experiential horizons. The ability to coordinate across continents paradoxically shortened planning timescales—every notification demands immediate attention, collapsing "later" into "now" and making sustained long-term focus nearly impossible.

Artificial Urgency and the Collapse of Temporal Hierarchy

Digital time doesn't just announce deadlines—it manufactures urgency through design.

Red notification badges. Bold unread counts. Countdown timers. "Last chance" language. Expiring offers. Streaks you'll "lose" if you don't act today. Limited-time access. Auto-advancing timers on consent screens.

These aren't neutral temporal signals. They're urgency engines—designed to make you feel time pressure regardless of whether the underlying task has time constraints.

The mechanical clock created real urgency through numerical countdown: five minutes until the train departs, two hours until the deadline. The urgency corresponded to actual temporal boundaries.

Digital time creates perceived urgency through interface design, even when no boundary exists.

An email marked "urgent" by the sender isn't more time-sensitive than one marked "normal"—but the visual signal triggers urgency response. A notification badge showing "47 unread" creates pressure to clear it, even when none of those 47 items require immediate action. A "limited time offer" expiring in 6 hours generates deadline pressure for a decision that could be made anytime, or never.

Temporal hierarchy collapses when everything signals urgency.

Pre-instrumental time had natural hierarchy: seasonal deadlines mattered more than daily ones, survival tasks outweighed convenience tasks. Mechanical time maintained some hierarchy: factory shift bells mattered more than personal preferences.

Digital time treats all temporal signals as equivalently urgent by default. The notification for a calendar meeting, a promotional email, a social media like, and a payment reminder all arrive with the same visual weight, the same interruption priority, the same implicit claim: "deal with this now."

You can configure notification priorities, but the default state is flat urgency—everything demands immediate attention until you explicitly downgrade it.

This inverts the temporal relationship. Instead of identifying what's urgent, you spend energy identifying what isn't urgent in order to filter the noise.

The result: urgency inflation.

When everything signals urgency, nothing is urgent—but you can't tell the difference without cognitive effort. Real deadlines get lost in manufactured ones. Actual time pressure becomes indistinguishable from designed time pressure.

Mechanical time made you late to a coordinate. Digital time makes you feel perpetually late to everything, whether or not any real deadline exists.

Asynchronous Coordination and Temporal Elasticity

Digital time unlocked something mechanical time couldn't: coordination without synchronization.

Before digital systems, coordination required temporal alignment. Meetings happened when everyone was present simultaneously. Phone calls required both parties available at the same moment. Collaboration meant shared time.

Digital time broke this constraint.

Email doesn't require the recipient to be available when you send it. Messaging apps let conversations unfold across hours or days with participants responding whenever convenient. Collaborative documents allow edits across time zones without real-time presence. Recorded meetings can be watched later. Asynchronous communication became infrastructurally possible.

This is digital time's genuine innovation: temporal elasticity in coordination.

You can work with someone in Tokyo while you're in New York without either of you adjusting sleep schedules. You can contribute to a project in your morning that someone else continues in their afternoon. Information flows across time differences that would have made collaboration impossible with mechanical time alone.

The cost: temporal ambiguity in expectations.

When does an email require response? Immediately? Within hours? By end of day? The technology enables asynchronous communication but provides no signal for expected response tempo.

Different people, different organizations, different contexts operate on different temporal expectations—but digital systems don't make those expectations legible. An email sent at 11 PM might be "just getting this off my desk, respond tomorrow" or it might be "this is urgent, respond now." The timestamp alone doesn't tell you.

This creates invisible temporal negotiation.

Every message, every notification, every request carries an implicit expected response time that you have to guess. Too slow and you're unresponsive. Too fast and you train others to expect instant availability. The right tempo is contextual, relational, culturally specific—but the digital system provides none of those signals.

Mechanical time had clear temporal boundaries: work hours, business days, shift schedules. Digital time's elasticity dissolved those boundaries. You can respond to work email at 10 PM on Sunday. Whether you should is unmarked by the system.

The flexibility that makes asynchronous coordination possible also makes temporal boundaries unenforceable. "Always available" became technically feasible, which made it socially expected in many contexts, even when no one explicitly required it.

Pre-instrumental time: coordination required shared environmental reading. Mechanical time: coordination required synchronized schedules. Digital time: coordination works across temporal distance—but at the cost of legible temporal boundaries.

What Digital Time Makes Possible—and Illegible

Digital time solved mechanical time's fundamental constraint: it enabled coordination across temporal distance without requiring simultaneity.

You don't need everyone in the same moment anymore. Teams collaborate asynchronously across continents. Information moves independently of people's availability. Work happens in handoffs across time zones rather than shared presence.

This unlocked:

- Global remote collaboration (distributed teams operating 24/7)

- Asynchronous communication (email, messaging, collaborative documents)

- Personalized scheduling (individual calendars replacing collective rhythms)

- Micro-coordination (real-time updates, location sharing, delivery tracking)

- Temporal flexibility (work whenever, wherever, with whomever)

Digital time made globally distributed coordination structurally possible.

But the multiplication of temporal reference frames also introduced new forms of temporal illegibility:

Temporal signals became incoherent. Mechanical time gave you one clock. Digital time gives you dozens of independent timers, alerts, and countdowns—all operating simultaneously, none aware of the others, creating obligations faster than you can navigate them.

Urgency became designed rather than real. Countdown timers, notification badges, and "limited time" language manufacture time pressure independent of actual deadlines. When everything signals urgency, nothing is legible as urgent.

Response expectations became invisible. Asynchronous communication works across time—but provides no signal for expected response tempo. The same technology that enables flexibility also obscures boundaries, making "always available" technically feasible and therefore socially expected.

Precision increased while legibility decreased. Digital systems track time to the microsecond but can't tell you whether now is the right moment to act. You can see every minute accounted for while losing the ability to read temporal appropriateness.

Reminder creation became frictionless, producing chaotic load. Setting temporal commitments takes seconds—subscribing to notifications, creating calendar events, setting reminders. Each seems reasonable in isolation. Together they generate incomprehensible, out-of-sync temporal noise.

Digital time didn't just accelerate mechanical time. It fundamentally restructured how temporal signals reach you—from single authoritative reference to multiple competing demands, from passive consultation to active interruption, from coherent hierarchy to flat urgency.

This is progress. Distributed work, asynchronous collaboration, and global coordination are genuine capabilities.

It's also loss. The ability to read temporal patterns, distinguish real urgency from manufactured pressure, and maintain coherent boundaries between temporal demands—these became nearly impossible when every app creates its own temporal reality.

The question isn't whether digital time is good or bad. It's whether we can read it at all.

Previous: Mechanical Time

Next: Social & Organizational Time →