Mechanical Time

How clocks abstracted time from environment and enabled coordination at scale.

How Humans Read Time — Part 2 of 5

→ Series overview

The mechanical clock didn't just measure time—it created a new kind of time.

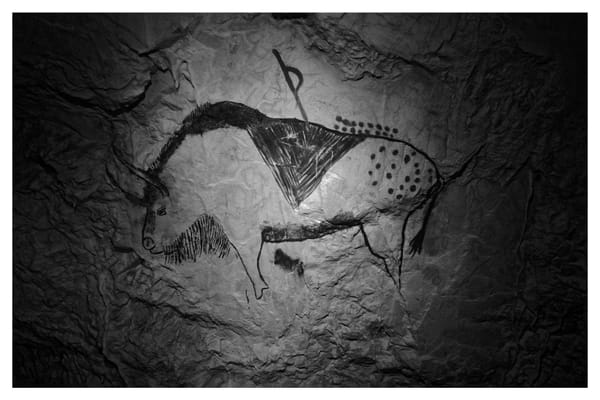

Before clocks, time was local. Each town, each monastery, each household operated on slightly different rhythms, synchronized loosely through visible signals—bells, sun position, shared routines.

The clock changed this.

It abstracted time away from environment and made it portable. A clock in London and a clock in Paris could show the same hour, even though their skies, seasons, and local rhythms differed. Time became a number that could travel independently of place.

This wasn't simply adding precision to what already existed. It was a fundamental shift in what time was—from contextual signal to standardized coordinate.

That shift unlocked coordination at unprecedented scale. It also introduced new forms of temporal discipline, new anxieties about delay, and new ways to be late.

What the Mechanical Clock Actually Did

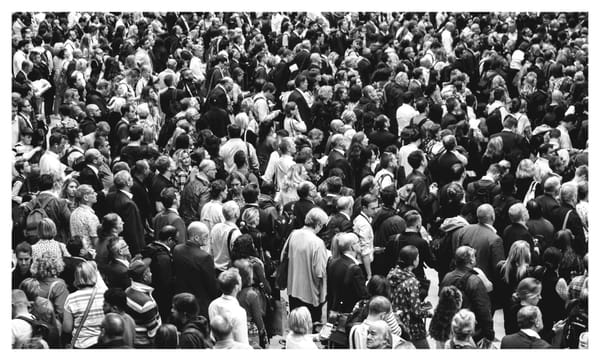

The first mechanical clocks weren't personal devices. They were civic infrastructure.

Installed in church towers and town squares, they announced time to entire communities at once. The bell didn't tell you what time it was for you—it told everyone what time it was for everyone.

This created synchronized reference points where none existed before.

Before the clock, "noon" was approximate—when the sun was highest, which varied by location and season. After the clock, noon was exactly twelve, regardless of solar position. The clock didn't follow the sun—it replaced the sun as the authoritative signal.

The immediate effect: time became detachable from local conditions.

You could now coordinate action without reading the environment. A meeting could be set for "three o'clock" rather than "mid-afternoon when shadows reach the eastern wall." The clock time was the same whether it was summer or winter, clear or cloudy, in the field or indoors.

Factories could operate shifts independent of daylight. Workers arrived and departed by clock time, not dawn and dusk. Production schedules could be planned months in advance based on hours available, not seasonal work windows.

Railways required this absolutely. Trains couldn't run on "when the station master thinks it's time"—they needed synchronized schedules across distances. A train leaving London at 10:00 AM had to arrive in Manchester when Manchester's clocks also read the expected hour. This forced standardization of time across entire regions, eventually nations.

The mechanical clock extended spatial coordination range while compressing temporal planning horizons. You could schedule across continents—but only in hours and days, not seasons and cycles.

Maritime navigation gained precision through mechanical chronometers. Longitude calculation required knowing exact time at a reference point (Greenwich) while observing local solar time. The mechanical clock made this portable—you could carry Greenwich time across oceans and calculate your position mathematically rather than through accumulated environmental observation.

This was the crucial innovation: time became an independent coordinate system.

It wasn't about anything anymore—it was a pure measurement grid you could overlay on any activity. Farming, manufacturing, prayer, travel—all could now be mapped to the same temporal reference frame.

The cost: time lost its semantic content. "Three o'clock" told you nothing about conditions, readiness, or context. It was just a position on an abstract scale.

Punctuality as New Temporal Discipline

The mechanical clock introduced a concept that didn't exist in pre-instrumental time: being late to a number.

Before clocks, you could miss a window—arrive after the market closed, after the ship sailed, after planting season ended. But you couldn't be "five minutes late" because minutes didn't structure social obligation.

The clock changed this.

Once time became synchronized and segmented into precise units, deviation from the number became measurable.

Lateness was no longer "missing the window"—it became "failing to arrive at the designated coordinate." This was a fundamentally different kind of temporal failure.

Factory bells rang at exact times. Arriving after the bell meant lost wages, disciplinary action, social stigma. The distinction between 7:58 and 8:02 became consequential in ways that "just after dawn" and "a bit past dawn" never were.

E.P. Thompson documented this shift in industrial England: workers resisted clock time initially because it replaced task-oriented rhythms (work until the batch is done, the field is planted, the repair is complete) with time-oriented discipline (work these specific hours, regardless of task completion).

This was also a shift from cyclical to linear temporal orientation. Seasonal rhythms—inherently cyclical, returning annually—gave way to linear schedules that marched forward in measured increments. The mechanical clock imposed sequence where cycles once dominated.

The shift was also moral. Pre-instrumental lateness was relational—you failed a person, missed a gathering, broke a social commitment. Mechanical lateness became systemic—you violated an abstract standard, failed to meet a coordinate. The guilt shifted from disappointing others to failing to comply with impersonal temporal order.

Task-oriented work maintained flow—you stayed inside the activity until completion. Time-oriented work introduced interruption—the clock bell pulled attention away from task to schedule, fragmenting continuous engagement into managed intervals.

The clock didn't just coordinate—it disciplined.

Punctuality became a moral virtue. Being "on time" signaled reliability, respect, industriousness. Being late signaled the opposite—even when the delay had no material consequence, even when environmental conditions (weather, distance, unforeseen obstacles) made exact arrival impossible.

Pre-instrumental time had slack built in through coarse resolution. Mechanical time eliminated slack by making every minute accountable.

This created new forms of temporal anxiety. You could now worry about being late before you were late—the gap between current time and deadline time became psychologically active space. The countdown itself generated pressure independent of the task.

Standardization and the Collapse of Local Time

Mechanical clocks didn't just coordinate communities—they eventually erased local time entirely.

Before standardization, each city kept its own time based on local solar noon. When the sun reached its highest point in Oxford, Oxford clocks read 12:00. When it reached its highest point in Bristol (2.5 degrees of longitude west), Bristol clocks read 12:00—even though this happened about 10 minutes after Oxford's noon.

This worked fine when most coordination was local.

It broke completely when railways connected cities.

A train schedule that read "departs Bristol 3:00 PM, arrives London 6:00 PM" was ambiguous—Bristol time or London time? Passengers missed trains. Freight arrived at the wrong hour. In 1841, two trains collided near Reading because one operated on London time and the other on local time—both thought they had the right of way at the same moment.

The solution: abolish local time.

Britain standardized on Greenwich Mean Time in the 1840s. Every clock in the country synchronized to a single reference, regardless of solar position. Bristol's clocks now showed the same time as London's, even though the sun disagreed.

This was temporal imperialism—one location's time imposed across geographic space.

The United States followed with time zones in 1883, driven entirely by railroad coordination needs. Four zones replaced hundreds of local times. Entire regions shifted their temporal reference point by minutes or hours overnight.

What was lost: time's connection to place.

"Noon" no longer meant "sun overhead"—it meant "the number 12 on synchronized clocks." Time became fully abstract, fully portable, fully detached from astronomical reality.

What was gained: coordination at continental scale. You could publish a train schedule valid across thousands of miles. You could schedule telegraph communications across time zones. You could operate factories in multiple locations on synchronized production rhythms.

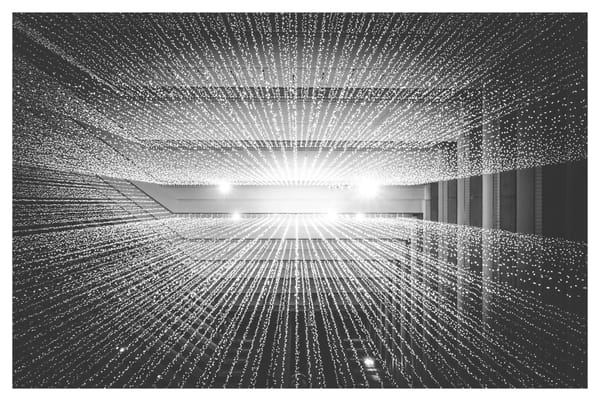

The mechanical clock transformed time from a local property into a global infrastructure.

Mechanical Precision and Temporal Fragmentation

The mechanical clock didn't just abstract time—it subdivided it.

Pre-instrumental time operated in chunks: morning, midday, evening. Mechanical time sliced these into hours, then minutes, then eventually seconds.

This wasn't neutral refinement. Each subdivision created new possibilities for control—and new forms of waste.

Frederick Taylor's time-motion studies in early 1900s factories took this to its extreme: every worker movement timed to the second, every task broken into optimized fragments, every "wasted" motion identified and eliminated.

The mechanical clock made this legible. You could now measure the difference between a 12-second task and a 15-second task, multiply across thousands of repetitions, and calculate "lost productivity" in precise terms.

Temporal resolution became a management tool.

The finer you could slice time, the more you could optimize it—or the more you could discipline deviation from optimal.

But high resolution cut both ways.

It revealed inefficiency, yes. It also revealed how much time was unaccounted for. Gaps between tasks, transition overhead, coordination delays—all became visible and therefore problematic.

Pre-instrumental time had no concept of "downtime" because time wasn't being measured continuously. You worked until the task was complete, rested when needed, resumed when ready. The rhythm was task-driven.

Mechanical time inverted this: tasks had to fit into time slots. If a task finished early, the remaining time became "empty"—a void to be filled with another task or else "wasted."

This created temporal fragmentation: the day broken into discrete units that had to be allocated, accounted for, and justified.

Calendars became schedules. Schedules became optimizations. Optimization created pressure to eliminate buffer, compress transition, and accelerate throughput.

The mechanical clock enabled unprecedented coordination. It also enabled unprecedented temporal compression.

What Mechanical Time Made Possible—and Impossible

The mechanical clock solved the fundamental problem of pre-instrumental time: it enabled coordination at scale without environmental intimacy.

You didn't need to know local conditions. You didn't need continuous attention to converging signals. You didn't need shared place or seasonal literacy. You just needed synchronized clocks and agreement on what the numbers meant.

This unlocked:

- Industrial production (shift work independent of daylight)

- Transportation networks (trains, ships on synchronized schedules)

- Global communication (telegraph, eventually telephone coordination)

- Financial markets (simultaneous opening/closing across locations)

- Scientific collaboration (experiments timed to the second across continents)

Mechanical time made the modern world structurally possible.

But the abstraction that enabled scale also introduced new constraints:

Time became interruptible. You could now "check the time" whenever you wanted—pulling your attention away from flow to consult an external reference. The clock broke continuous temporal orientation into episodic glances.

Urgency became numerical. Deadlines weren't approaching windows read through environmental signals—they were countdown timers. Five minutes before a deadline felt different than five hours, even if both were "enough time" for the task.

Punctuality became absolute. Being late wasn't missing a window—it was deviating from a coordinate. The difference between on-time and late became arbitrary (why is 9:01 late but 8:59 acceptable?) yet socially enforced.

Time lost flexibility. Pre-instrumental coarse resolution created natural buffers. Mechanical precision eliminated them. "When the soil warms" allowed weeks of variance. "March 15th at 9:00 AM" allowed none.

The mechanical clock didn't just measure time more precisely. It restructured human temporal experience—from reading flow to tracking points, from environmental sensitivity to numerical discipline, from local rhythms to global synchronization.

This was progress. It was also loss.

What came next—digital time—would take the abstraction even further.

Previous: Time Before Instruments

Next: Digital Time →