Time Before Instruments

How humans read time before clocks — through environmental signals, rhythm, and anticipation.

How Humans Read Time — Part 1 of 5

This article is part of a five-part series on how humans and organizations read time.

→ Series overview

Before clocks, humans still knew when to act.

Not precisely—but reliably enough to plant, harvest, migrate, hunt, and coordinate across distances without watches, calendars, or synchronized time zones.

Time was read, not measured.

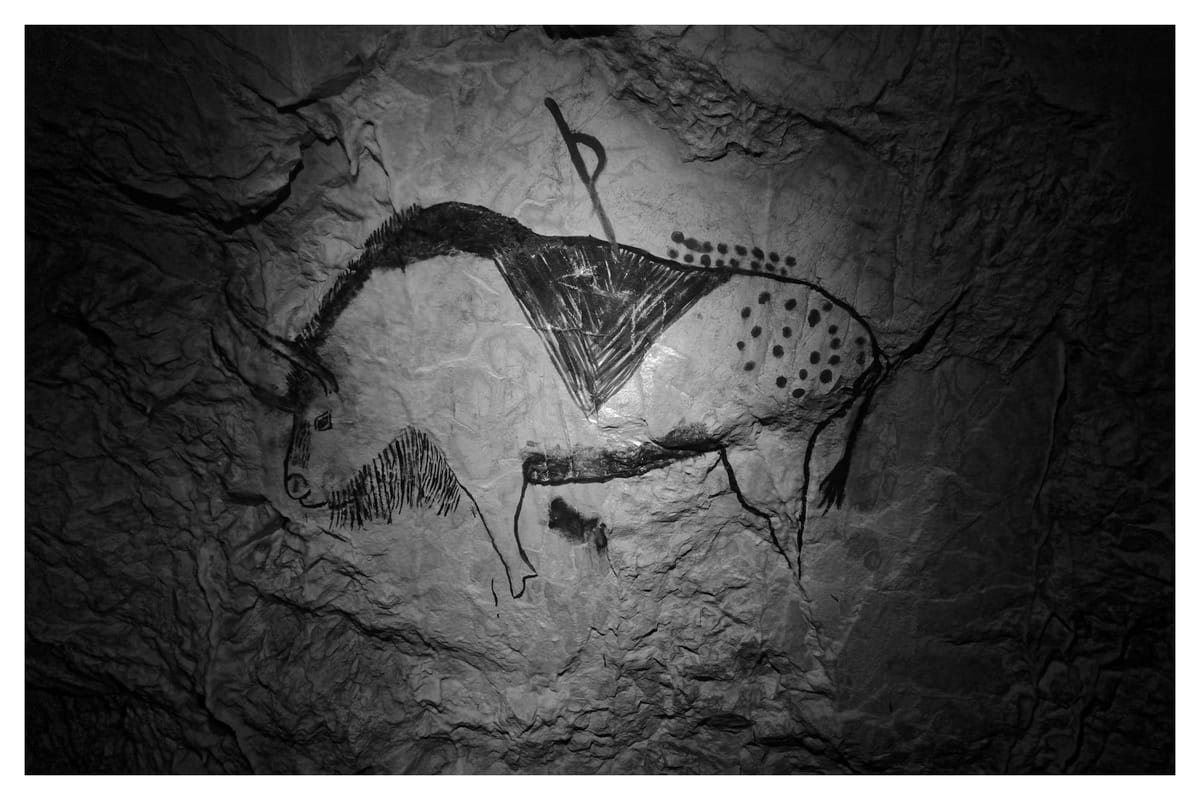

The signals were everywhere: light quality, shadow length, star position, animal behavior, plant growth, temperature shifts. These weren't approximations of "real time"—they were time, in the only form that mattered for action.

This wasn't primitive guesswork. It was a different kind of precision—one built on pattern recognition rather than instrumentation.

A note on scope: This series observes temporal reading primarily through Western industrial development—societies that moved from agrarian environmental time to mechanical factory time to digital knowledge work. Similar transitions happened elsewhere, often differently. Lunar calendar cultures layered linear coordination over persistent cyclical patterns rather than replacing them. Many societies maintained environmental time reading alongside mechanical synchronization. What's described here is one trajectory among many, not a universal human story.

What Pre-Instrumental Time Reading Actually Looked Like

The sun didn't tell time by position alone—it told time through qualities.

Morning light has a different angle and color than afternoon light. Shadows stretch differently. Temperature rises and falls in recognizable patterns. A person working outdoors doesn't need to check the hour—they read the signals' convergence.

This is pattern-based time reading: multiple environmental cues cross-referencing each other.

Sailors navigated by star positions, wind patterns, water temperature, bird migration routes, and cloud formations. None alone were sufficient. Together, they formed a temporal map reliable enough to cross oceans.

Agricultural societies operated similarly. Planting wasn't determined by calendar date—it was determined by soil temperature, last frost signals, day length, and local plant indicators. Farmers didn't "estimate" planting time—they read it from converging environmental data.

Time reading was cyclical by nature—patterns repeated, knowledge accumulated through recurring observation. Linear progression mattered less than rhythmic return.

The key difference from instrumental time: context was inseparable from signal.

You couldn't read time without reading the environment. Time wasn't abstracted into a number—it remained embedded in the conditions that made the reading relevant.

Temporal Resolution Without Precision

Pre-instrumental time reading operated at coarse resolution by design.

You didn't need to know it was 3:47 PM. You needed to know: morning work window, midday heat, afternoon before dark, time to return.

This wasn't lack of sophistication—it was appropriate granularity for the decisions being made.

Monasteries used canonical hours (Matins, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, Compline) to mark rhythm boundaries for prayer, work, and rest. The exact duration of each period varied by season and latitude. That variability wasn't error—it was correct time reading for the activity structure.

The resolution matched the task.

Long-cycle activities (migration, seasonal preparation, generational knowledge transfer) were read in weeks, moons, or seasons. Short-cycle activities (daily work rhythms, meal timing, social coordination) were read in sky position and environmental cues.

What looks like imprecision from an instrumental perspective was legible temporal structure: readable, actionable, and socially coordinated without requiring synchronized numerical agreement.

Different communities could operate on slightly different timing and still coordinate effectively—because they were reading the same environmental signals, not synchronizing to an external standard.

Coarse resolution created natural buffers. "Plant when soil warms" isn't procrastination-compatible—the window is wide enough to start, narrow enough to matter. Urgency emerged gradually through converging signals, not suddenly through deadline approach.

Anticipation as Temporal Technology

Without instruments, time reading became anticipatory rather than reactive.

You couldn't check the time whenever you wanted. You had to develop the capacity to recognize approaching transitions before they arrived.

A shepherd reading weather patterns wasn't observing current conditions—they were reading direction. Cloud formations, wind shifts, animal behavior, and atmospheric pressure (felt, not measured) converged into anticipatory signals: storm coming, clear window closing, safe passage narrowing.

This required continuous environmental attention.

Pre-instrumental time reading wasn't episodic (glance at clock, return to task). It was continuous pattern monitoring—a background process that sharpened sensitivity to temporal boundaries.

Hunters developed this acutely. Tracking wasn't just spatial—it was temporal. Footprint depth, vegetation disturbance, scat moisture, scent persistence: these signals told when an animal passed, how far ahead it was, whether pursuit was viable within remaining daylight.

The skill wasn't reading time at a point. It was reading time as flow—recognizing approach, detecting acceleration, sensing exhaustion of windows.

This kind of pattern-based temporal anticipation isn't extinct. Operations managers in modern manufacturing facilities read production flow the same way—recognizing when a line is approaching capacity limits before metrics show it, sensing when rhythm is degrading before breakdowns occur. Air traffic controllers read traffic patterns, anticipating conflicts before they materialize. Emergency room triage nurses read patient deterioration, detecting the shift from stable to critical before vital signs alarm.

These aren't vestiges—they're active professional capabilities that work exactly like pre-instrumental time reading: continuous pattern monitoring, anticipatory signal recognition, reading flow rather than checking coordinates.

The cost: this kind of time reading required deep environmental familiarity. It didn't scale. It didn't transfer easily across contexts. It couldn't coordinate strangers.

What Pre-Instrumental Time Reading Required

Time reading before instruments demanded three things:

Environmental intimacy. You had to know this place—its rhythms, signals, exceptions. Knowledge didn't transfer easily. A coastal navigator couldn't read time inland. A forest hunter couldn't read time on open plains.

Continuous attention. Temporal signals weren't available on demand. You couldn't "check the time"—you had to maintain ambient awareness of converging cues. The skill was staying oriented, not looking up. You couldn't interrupt your attention to check time—orientation was continuous, or you were lost.

Tolerance for coarse resolution. Coordination happened through shared environmental reading, not synchronized precision. "When the shadows reach the marker" was sufficient agreement for collective action.

This wasn't romanticizable. It was constraining.

It limited scale, prevented standardization, and made coordination across distance nearly impossible. You couldn't schedule a meeting three towns away for a specific hour—you could only agree on a seasonal window and hope your readings aligned.

But it had one property mechanical time would eliminate:

Time remained contextual.

You never read time without simultaneously reading conditions (weather, daylight, season), resources (energy, materials, capacity), and relevance (whether now was the right moment to act). The signal and the situation were inseparable.

When clocks arrived, they didn't just add precision—they abstracted time away from context.

That abstraction unlocked coordination at scale. It also created new forms of temporal blindness.

Next: Mechanical Time →